In memory of an extraordinary artist who has left this world. You will be missed, dear friend. Thank you for all the treasures you left to us. Your beauty will live on as a testimony of your exceptional skill and your wondrous vision.

Rest In Peace Patrick Alt, April 1950 – July 2013

It is with great honor that I was given the gift of interviewing masterful photographer, artist, and extraordinary human being, Patrick Alt. In the company of his dear friend and fellow photographer, Nina Pak, he reflected on his life, and shared his final insights with us before passing from this world. It is my privilege to present to you the words of the most brilliant and fascinating, Patrick Alt. – Jacqueline Ryan

Exclusive interview with Patrick Alt by Jacqueline Ryan

Q: What is your history as an artist and photographer? Do you have formal training or were you self taught?

A: I went to Cal Arts for my Junior and Senior year and got my BFA there, and I was doing these enormous 7’ x 11’ foot abstract paintings, and my first wife’s mother was a grand doyanne of the fashion industry at the time and she would go to Japan and Asia, she would check on fabrics and patterns and stuff for the lines that she was involved in at this company called Campus Casuals and so she came back one day from one of her trips and she had brought back a brand new Pentax Spotmatic camera and I thought well that’s really neat because you know, I would not be adverse to having a camera to photograph my paintings…

That’s all my intention was I never intended to be a photographer. Once I got the camera, it was a Spotmatic 2, it was one of the most advanced cameras on the market at the time, this would have been 1971, and I just took to that little toy like fish to water and I was just so mesmerized by the process of image making, and so I took one class of photography and one of them was done by a graduate student and it’s like, “Okay, here’s the chemicals, you pour it in, shake it up, pour this in, and shake it up, pour it out, and I’ll see you guys later,” and that was the full extent of my photo education. So, I went through the rest of my… all the way to my masters, without any further formal education in photography. The rest is self taught. Everything I’ve ever done: my architecture, my furniture design, all of that stuff has been self taught. I’m a firm believer of that.

Q: “He’s such a Renaissance Man.” You are very good at your craft at every art form that you picked up.

A: I make my own cameras from scratch or restore it.

Q: Can you tell us about that, Patrick, and about how building your own cameras ties into your inspiration and the platinum printing process?

A: I evolved as many large format photographers do. They start with 35, and so from ‘71 to ‘78 I was shooting 35mm, and then in ’78 I got a two and a quarter camera – a Maya 645, which really changed a lot because the negative is two and half times larger than a 35mm, so I was making these little 5 1/4” x 8 1/2” inch 35mm prints, and from there went to 16” x 20” inch prints because doing this scale paintings I’ve always liked large images. And then in 1980 got all the money together to buy a 4” x 5” and that was a life changing experience to say the least.

Q: How so?

A: Because of the size of the negatives and the clarity so that I could make these 20 x 24 inch prints that were as razor sharp and were absolutely as tonally beautiful that I was never able to do before, and you feel like a big kid finally. Funny, when I bought that camera I thought, “God, this is the biggest camera I’ll ever use…” Now it looks like something you’d get out of a Cracker Jack Box.

Q: You started to build your own cameras after that.

A: I got that in ‘80 – ‘81 and shot like 15,000 negatives for the next ten years, and then a friend of mine turned my on to platinum printing and I just thought, “Oh my God this is my medium. You know, everybody eventually finds their medium, finds the process that directly influences the way that they see the world, and platinum is such an exquisitely beautiful process and with the full tonal range and color, it’s just an incredible thing, and so as a result of that, because platinum printing is a contact print, the only thing I was able to do at the time was to do 4 x 5 contact prints… Well, those are a little to small for me and so I ran into, you know, you have these pivotal moments that literally five minutes later that would have changed the course of your life? Well, luckily this one didn’t…

I ran into a friend of mine coming out of one of the camera stores as I was walking in and we got to talking and he said he had this 8’ x 10’ camera in his garage – it had all been taken apart and some of it was sanded and stained with water based walnut stain, it was just terrible, and he said Do you want it? and I said “Yeah,” so I traded him one of his photographs for it and I took it home and i restored it, stained it, polished the metal, did all of this work on it, you know, the first time I’d ever done it, and from that my friends saw it and said, “Oh my God, I’ve got one, can you do mine? Do you mind?” And the next thing you know I have a three year waiting list for me to restore their cameras, and so during the way, you know, I got call from this guy who wanted a 4” x 10” camera and I said well, let me think about it, let me design it.

I came up with this fabulous design for it and I made ten, sold them all, I then made twenty six – they’re all beautiful, they’re made out of Australian lace wood and black metal with gold knobs and gold screws, it’s really an exquisite piece of work and I also made five 8”x 10”s… Well, 8 x 10’s normally weigh about 12/13 lbs. – mine weighed 7 1/2 so it allowed me to go back out into nature again, carrying the 8”x10”… because my 4”x5” was only 4 lbs. and I got a new tripod that was 3 lbs. less so I was basically carrying the same amount of weight except the film holders – the film holders were incredibly heavy, but I worked around it and dealt with it and so I was able to shoot nudes again outside which I had done a lot of during the 80’s and I was able to make polymer prints of these. And as I got more and more into the larger format community, people would come up to me and say, “Listen I’ve got this large format camera and I’m never going to do anything with it, would you like it?” So I bought a 12”x20” banquet camera, an 11”x14” camera, a 7”x17” panoramic, then I got a 14”x17” – I got two of those – I have fifteen cameras… I have five 8”x10”’s just by themselves… and then by this time I had achieved such a national reputation for the quality of my work, that occasionally one of my cameras comes up on ebay and it gives top dollar because of the reputation that I have established for myself… so these cameras were so meticulously crafted, there would be like thirty coats of laquer on them, all the brass was repolished and lacquered, I’d even polish the heads of the screws and lacquer those.

Q: You are a masterful perfectionist, aren’t you Patrick?

A: I am a perfectionist, there is no question about it.

Q: So these are real works of art and collector’s items and people get that…

A: So, when people would get… when I would ship the cameras to them, they’d open them, I would get, “What have you done to me? It’s too beautiful to use.” and that happened virtually every time and it’s always nice to do something for a client that exceeds their expectations. So, that was something that I got great pride in, and you know, it’s nice to be able to design my own camera.

Q: “You had a name for your cameras didn’t you?”

A: Alt Views, yeah, Alt Views.

And then I made what I think was the most beautiful camera ever made in the history of the world, if I can be so humble, an 11”x14” pinhole camera made out of African zebra wood. But I’ve never really been able to use it, so now I have a friend who is going to get a big surprise as I got ascention in my work *** weed my tools out of my life, so he’s going to get this little 14 Pinhole Camera.

Q: It’s incredible that you were willing to take them out into nature. You would have to be really determined and passionate about your subject. I would really love for you to speak to me about what inspired you… What kept you going? I would like to know where that comes from for you?

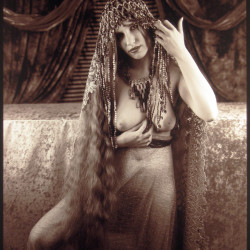

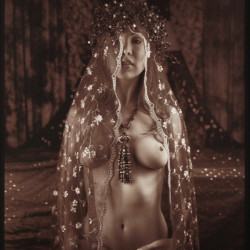

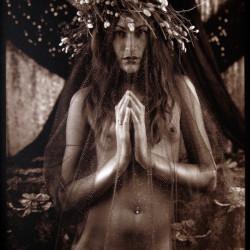

A: It’s an interesting thing in the sense that we have such a history of mythology – especially Grecian mythology regarding women and the landscape… Tree nymphs and water minads and muses and all kinds of stuff and you know, so we have all these images of these naked women running around the forest and so one of the things I have always been interested in tapping into is that kind of mythology, which is where it kind of developed further, that’s where the Goddess Images came out of.

Q: They are spectacular to say the least… And elaborate and sensual and erotic and beautiful and there is a theme there with veils and headpieces. I’d love for you to talk about that.

A: As my reputation as a camera guy kind of got spread all over the country I got a phone call or an email from this guy who had a mammoth plate camera which is an 18”x22” camera which is enormous (there should be a picture of me somewhere of me standing next to this big camera, on my website?) So he said, “I’m trying to sell it, I don’t know how much it’s worth… Can you help me out?” So I said, “Well, there’s only probably half a dozen people in the country who would be brave enough to tackle a camera that size – because it really is, it’s a very arduous camera to work with, and the camera is 37 pounds and the tripod is 15 by the time you get the lens, you’ve got a hundred pounds of camera equipment there… So, and I have taken it out…

I haven’t done any nudes outside, but I’ve done some landscape work with it, which was always kind of fun to work with. And so we got that going, and as I started slowly mastering what the camera was capable of, because when you have an 18” x 22” contact print (because you cannot enlarge it) it’s really extraordinary, because you have to look at the size of the negative in regards to the size of the finished print, and what’s called the degree of enlargement. So if 35mm negative blown up to an 8” x 10” is the same degree of enlargement as a 4” x 5” negative blown up to 30” x 40”, an 8” x 10” blown up to 5’ x7’ feet, and a mammoth plate blown up to 25’ x 35’ feet. It gives you a little perspective as to what kind of quality these prints have, especially now if they’re just contact printed, and there’s absolutely no grain whatsoever, so there’s a smoothness to them that’s very extraordinary because most of the time you look at photographs and the grain of film, you see that as skin tone as whatever smooth surface, you always see this grain there, and to all of a sudden to have photographs where there’s no grain, even from an 8”x10” contact print, there is no grain whatsoever, makes the image particularly extraordinary as a physical object and so what happened is, it took me a year and a half to build up the courage to tackle restoring the camera because it was complete, but the bellows were completely shot, the brass was literally black all over, it had tarnished so badly, the varnish had gotten to be really ugly, so to taking this monster thing apart into all its component pieces and then doing all that was necessary to restore it, it took two solid weeks… but that was working every day – and then it has these extraordinary layers of contemporary furniture grade lacquer on it so it has this silky, sensuous color, and I did it in a dark red mahogany stain, the stain is really quite gorgeous in and of itself, and then had re polished all these little brass pieces, they all had to be lacquered otherwise they would be tarnishing, and so that was something that was certainly a job to tackle.

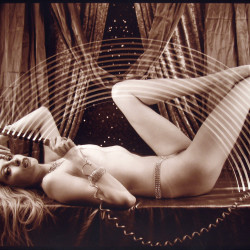

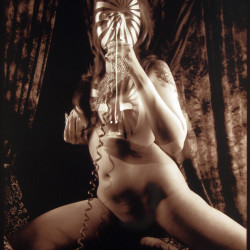

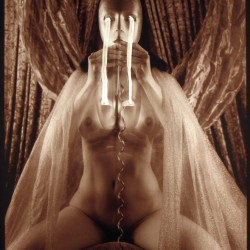

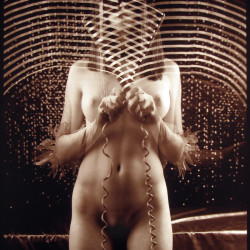

We moved into our new house in Culver City and I was actually able to set up a small little working studio and I was starting shooting the figures here and mostly kind of simple figure studies as I was finding my way with it and what the thing was really capable of doing. The first body of work that came out of this was the motion series. Very very bizarre, strange and interesting, because there is an enormous amount of serendipity involved because you don’t know what you’re gonna get and what the cameras are going to see until you develop the film.

Q: That’s part of the magic for you right? The excitement of seeing the ultimate results?

A: Absolutely! It’s like, what are we going to get out of this one? And more often than not they just turned out quite extraordinary. I’m always looking around for props and different things. First, I found this wreath that was like a perfect headdress and I tried it on one of my models and put some fabric in there, nothing else, just pretty simple but all of a sudden it just generated this whole new direction which just got more and more complicated so it moved out of the motion series which had run its course, it was like five years of work, and then into the next five years which was the Goddess images.

There is so much detail and so much serenity…

One of the things that happened is that… I’m always drawn to really powerful, intelligent, ambitious women, you know, I married one, so that’s something about women that I’ve always been drawn to, and what the goddess image is about for me is a feminine power, kind of a pre-patriarchal world view where women were a lot more valued in their cultures than they are in many cultures now, and um, I found it very interesting – often times models and I would collaborate on putting this regalia on and I found it very interesting that there was a complete sea change in their attitude once they were dressed like that. They took on a persona of this powerful feminine figure, and power in a very different way of masculine – masculine power is a very different kind of power, masculine power seems to be much more about strength, where women’s power is about love and nurturing and giving birth and new life and all of that stuff. So that’s kind of where that came from and it also allowed me to push the envelope to much more explicit, erotic imagery because it totally fit in to that whole iconography of what that was all about. So I worked on those until I ran out of film because I needed another fifteen thousand dollars to buy enough film to order it, because you have to buy an entire production run to do this and that’s not cheap, but then I got so sick that my photography days are over.

Q: That’s just terrible… It makes me so sad.

A: So it’s really hard to think about all this stuff that I still have in my mind and all the stuff that I haven’t printed yet. I mean, right now I have a young assistant who’s helping me label negatives and stuff and going through those… There are literally hundreds of photographs that have never been printed and will never be printed.

Q: Can’t you give someone the rights to print?

A: No, ‘cause this is a printing platinum and it’s a very particular way of doing things. No, it just is what it is. It’s not as if I don’t have truckloads of stuff… We refer to it around here as art by the pound… It’s so much stuff…

Q: So then the goddess series was your most recent project that you were working on?

A: Yes, yes…

Q: What about the Pow Wow Series?

A: That’s kind of been done for a while. And that work is… you know, one of the thing’s that any artist faced at the end of their life, is what happens to their work? And uh, especially if you’re not a major league blue chip artist yet.

Q: Well yes you are, you certainly are…

A: But nobody else knows that.

Q: Just because the world doesn’t recognize yet, but they will, I’m sure of it.

A: As somebody told me once, “You’re the best photographer in America that nobody knows about.” That and four bucks will buy you a cup of coffee.

Q: Well, Patrick, you will be known… We’ll do our part.

A: I appreciate it. I literally don’t know how much longer I’m going to be around, so I’m doing as much as possible, so right now what I’ve been working on are books – these big twelve inch square photo books.

Q: Please tell us all about your books, we’d love to know about them and spread the word about them and let people know that they’re out there, and share your work.

A: I’ve finished six books so far, there’s another one in process… They’re in the process of doing a sample book, and then they’ll do a production run. I always just have twelve done.

Q: What are the books about?

A: They’re all my nudes. I have a complete book of the goddess images which is called the Avatar of the Sacred Feminine, and the quality of the book is just astounding, it’s just absolutely astounding. I can’t imagine how anything digital could turn out to be this good but it does.

And then the second book is called Luxe et Flux, which is light in motion, and that’s the motion series.

I’m trying to come up with interesting names for the books, and my brother and I are doing all the designing together and he has become a master at the program that this company lets you use to put a book together.

And then I have Pools of Desire which is swimming pools, so it’s shot during the day and shot at night, nudes around swimming pools, and that’s pretty wonderful.

And then the three that we’ve got is 29 Palms which is a combination of still life and nudes out in Twenty Nine Palms.

And then I did a book of Erin, as smaller one, and 8×8 – a favorite muse and a wonderful artist herself, so we designed this tiny, well tiny compared to 12×12… it’s just wonderful of all the nudes that we’ve done out in the world for the last seven years, and the last one is Anatomica Notura which is nudes in the landscape.

Q: And what do these books mean to you, Patrick?

A: It means that you can sit down and look at a body of work at one time, and that it’s kind of a legacy… Basically, it’s all about legacy. And then the one that’s in works now is called Night Flashes, and that’s using a Holga camera and photographing nudes at night around the city.

Q: And these models were really kind of opening their coats and flashing while you took their picture quickly.

A: They would flash me, and I would flash them.

Q: What fun! Guerilla photography out in the city!

A: Exactly. It’s a lot of fun to do because it makes you feel like your gettin’ away with something. The Holga takes a square image so what I do is I always challenge myself to do something different so I turned the camera on its side and made diamonds, so the images are diamonds.

Q: You have a close personal relationship with a lot of your models and muses… Could you touch on that?

A: That’s one of the great side benefits about what I do… is that I’ve established this extraordinary relationship with so many different young women. I’m like their kindly old uncle. They just love me and are very concerned about me and call me all the time and some of them have been friends for twenty some years or more that have been my muses for such a long time.

Q: You find there’s something new and interesting photographing them over and over again?

A: Absolutely. It’s an amazing thing because it becomes an extended portrait. Each time you work together, your hair’s a little different, weight’s a little different, certainly the place is usually different, and as a result the pictures are different but it’s still the same photographer, still the same model, but it’s a different location and each location generates new kinds of imagery, and it’s like I learned many years ago, if I took a model out to the desert, that because of the harshness of the desert and all of that, she would become a form – another natural part of that landscape and would just become an object like another rock or something like that… But if you go up to the forest, she becomes an inhabitant of the forest, and there’s a very different, completely different dynamic going on when that happens, so um, a number of years ago I gave a talk at one of the APIS conferences about portraits with the large cameras and I said one of the things: I’m real interested in portraits and most of my work is… the face is always showing.

Most photographers, for some reason, they want to hide everything which gets boring after a while. And I said, “You know, when you have a figure and she’s hidden, she becomes an object, but when she’s photographed and you can see her face whether directly as a portrait or just glancing off to the side, she becomes a subject, and it’s a very different dynamic, so I’m not interested in doing women as objects, but images as subjects.” It makes a big difference. Because, you know, I love the women I work with, for the most part except for the occasional whackadoodle that enters my life, but one of the things that happens is, when you do this and you go take your clothes off for somebody is it accelerates the intimacy of your friendship very quickly because it establishes a very powerful bond of trust that’s required for any kind of a deep and long lasting friendship, so that everybody I’ve ever worked with has been totally able to trust me in regards to not doing anything inappropriate.

Q: It really shows in their eyes and poses. They’re natural and you can feel that, they look completely relaxed.

A: Also, I don’t tend to pose people. What I do is what I call editing people in space. So I work with everybody’s unique body language and I’ll say, “Stop, that’s perfect, don’t move.” Sometimes I’ll adjust a little bit here, a little bit there, move a hand, you know whatever, but for the most part I let them do what feels right for them and that’s why the images have the power that they do.

Q: Even in the more explicit goddess photos where their legs are spread open and they’re looking in the camera, there is no vulnerability there whatsoever, it’s just powerful.

A: It’s about women’s sexual power which has been shut down or exploited in very awful ways, that to make an image like that is a very challenging image to do because of that history of exploitation in porn and stuff, and so there’s this thin line between porn and erotic and it’s dancing that line so you know that even though the compositional arrangements are the same, the psychological differences are enormous.

Q: That translates through the images… It’s extraordinary.

A: Those that do tend to be the ones that stay on as friends “get it.”

Q: I’d like to know a little bit of background, like if your family had a creative history.

A: There’s no other artist anywhere in the family.

Q: So where did this come from do you think?

A: They figure I was the result of a stray cosmic ray, that’s messing up with my genetic predisposition. I went to college as a marine biology major, and never had an art class, never had… It was just never on our radar screen. Nothing whatsoever.

Q: So something flipped a switch with you at some point.

A: What happened was when I went off to university, I said I couldn’t do hard science anymore so I changed to undeclared and started taking various liberal art classes and so what happened was, I took this one figure drawing class that allowed me to draw the figure for the very first time and it was like, “My God, this is it! This is what I was meant to be.” Talk about turning the light switch on. Within about two weeks, this incredibly long, involved, depressing, post adolescent identity crisis disappeared. I knew exactly what I wanted to do and who I was, and when I went home for spring break I told my dad that I changed to art major and he kicked me out of the house.

Q: So did you just leave the house and continue on?

A: I left the house and continued on. There was no question, and being the workaholic that I am, I went through six years of art school all the way to my masters.

Q: Were you able to resolve that with your father later?

A: Finally, finally… finally… but, it was something that was a big deal, ‘cause one of the realities of being a student artist is that 95% of kids who go to art school drop out and never make art again after school is over… because it’s those few who have the passion, the right combination of things to continue doing this basically worthless activity that nobody gives a shit about. So, over the years I’ve been thinking a lot about what it is, about what I do and how it’s achieved and the components necessary to become an artist and there are basically three things: You have to have talent. I mean, that’s kind of the most obvious, you have to have the ability to say something. The second is ego, you have to believe in yourself strongly enough to get in the face of enormous indifference – nobody out there gives a damn whether you’re an artist or not, if we all stopped nobody would really care. And the third is discipline – you have to work at it all the time. Discipline and perseverance. You have to have all three of those and if you don’t have all three of those, it’s never going to happen.

I don’t have a choice, it’s who I am, and making art is like breathing, so…

Q: What are your greatest achievements?

A: There are several. One is my house that I designed and built. I got to build my house and design it down to every single doorknob. It’s a house of art, you walk in every spare bit of wall space is taken up with paintings or photographs. So my wife and I have this arrangement that she makes the money. She buys and I trade.

You know, it’s hard for me to say because I’ve started painting again after several years. I had stopped for twenty six years. Paintings are completely and totally different, they have absolutely no relationship to the photograph whatsoever. You would never know in a million years that the same person did both processes.

Q: What made you want to come back to painting?

A: I’ve always loved painting, I’ve always loved doing it, and let me tell, after twenty six years, the inertia of not working is incredibly powerful so it actually took me several years of thinking about it before I actually got it together to start working. I’ve been doing these big paintings on paper, ‘cause I don’t have a studio to canvas or storage for them, so they’re like 29”x41” pieces of beautiful rag paper and that I paint on top of things. So I’m real interested in stripes and symbols, so most of them have little crosses, triangles, diamonds, different things that have if, anything they coincide with a kind of archetypal imagery that the goddess series is about.

My achievements is knowing that… all the work I have done in my lifetime, which is my friends are completely blown away by the amount of work that I have done in my life, and they all say how… I work every day – I did work every day – even being as sick as I am now I’m still getting books done. So I love my teaching, I have twenty two years of teaching and the influences I’ve had over all these young minds. Which is huge.

Q: You taught at UCLA?

A: UCLA Extention Interior Design Program and I taught furniture design.

Q: And you are self taught in…?

A: Everything. Everything.

Q: It makes sense though, when you’re working with wood and stain and form when you’re building cameras, it’s not that big of a leap then, is it, to building furniture?

A: No, it’s not.

It’s important if I’m doing an exhibition that I’ve either made the camera or restored the camera to shoot the film with. The film is all processed by my hand, I make all my own prints from scratch, cut my own mattes, build the frames, put them all together so that everything up on the wall is done by my hand, and there is a huge emotional satisfaction about that. So it’s impossible for me to let anybody else do that, it’s just who I am. You know, I can do it myself. It’s a passion, you know

I live to work and I have this… One of the problems with many artists – especially when they reach around fifty – they’ve gotten to the point where they’ve learned their craft and they’re doing some nice work and they never do anything different ever again. I have this one little chant on my back that’s always pushing me to try new things, so whether it’s shooting a Holga at night, doing goddess photos with the Mammoth plate, doing nudes outside with the 8×10, building these photo constructions that I did, all that stuff is part and parcel to… it keeps me engaged.