Amanda Manitach’s collection of ephemeral new works is on offer at Seattle’s Bryan Ohno Gallery in the International District. The work is on display until March 1st, 2014. Below, Miroir correspondent Siolo Thompson asked the artist some questions about her work, her artistic practice, and her obsessive nature.

Q: In the past your work has drawn on transgressive avant-garde modernism in particular Lustmord (sexual murder). What is it that you find compelling about this combination of death and sex? Why does your work often balance between those two poles?

A: Cf. The history of art and everything.

Or here’s a quote I really love that may or may not adequately speak to this:

What, indeed, is the meaning of the death of God, if not a strange solidarity between the stunning realization of his nonexistence and the act that kills him? But what does it mean to kill God if he does not exist, to kill God who has never existed? Perhaps it means to kill God both because he does not exist and to guarantee he will not exist – certainly a cause for laughter: to kill God to liberate life from this existence that limits it, but also to bring it back to those limits that are annulled by this limitless existence – as a sacrifice; to kill God to return him to this nothingness he is and to manifest his existence at the centre of a light that blazes like a presence – for the ecstasy; to kill God in order to lose language in a deafening night and because this wound must make him bleed until there springs forth ‘an immense alleluia lost in the interminable silence’ – and this is communication. The death of God does not restore us to a limited and positivistic world, but to a world exposed by the experiences of its limits, made and unmade by that excess which transgresses it.– Foucault

Q: Among your artistic influences you cite 19th century art and literature, the Vienna Activists, hysteria, and the secular appropriation of religious ritual. Can you speak to these influences and to their manifestations in the work you produce?

A: I see it all interlaced. The 19th century saw the emergence of Darwinism, atheism, modern cities, mass media. Hysteria was a female-focused expression of social malaise and formlessness, physical and psychological distress born of that era and of those situations. I would argue we’re still firmly bogged down in the same dilemmas of the era.

Then of course, the classic gestures of the 19th century hysterics are incredibly similar to the physical gestures of both classic demoniacs and contemporary Charismatic Christians. (The French doctor and pioneer of neurological studies Jean-Martin Charcot and his artist sidekick Paul Richer documented these similarities in the book Les Demoniaques dans l’art, published 1887.) Because of my background as a Charismatic pastor’s kid, I’m fascinated by the recurring imagery connecting the possessed, the hysterics and present day Charismatics: the back bends (Charcot called it the “arc-en-cercle”), the spasms, the nonsensical babble (like glossolalia).

The Vienna Actionists were a generation exercising a similar vocabulary of movement and theatricalized sexuality and violence. This was a generation who were little kids during the Holocaust and WWII and who grew up Catholic. Some of their work is barely tolerable, but their mythological spin on violence, ritual and the body is fascinating and more up to date, of course, than the quaint image of the hysteric.

I’ve settled on making work that loosely circles this subject because it’s what I know. I grew up in a psychologically-damning intersection of sexual repression, exorcisms (I was exorcised twice as a teenager, once for an eating disorder), faith healing and ecstatic demonstration that finds echoes throughout culture and history. It’s thrilling and terrible and mysterious.

Q: Many of the artists and writers that you cite as important to your development engaged in some form of automatic writing or drawing. Can you speak to that tradition? What is ‘automatic drawing’ and is it part of your personal process?

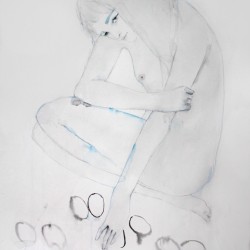

A: I’d call my drawing style more or less automatic. I rarely use any kind of reference. Even with figurative work I start with a total mess of inconclusive scribbles and gestures and go from there. Some of my larger abstract graphite pieces, like Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, are completely made using a meandering, automatic type of mark-making. It’s addictive. And ecstatic. You lose yourself.

Q: On the other hand there is obsessive drawing and drawing as ritual, an art form often considered in the cannon of ‘outsider art’. Clearly a part of your artistic and curatorial process, is obsession at the root of your practice? Where does that stem from? (Reference to Over and Over: A Small Survey of Obsessive Drawing)

A: I’m an obsessive person. I use the term too often to describe my processes and interests, but I love monomania, the idée fixe channeled through art practice. I love obsessive people. People who aren’t obsessed are (forgive my generalization) boring.

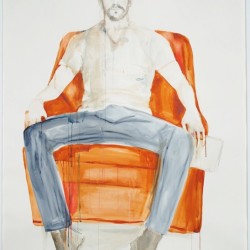

Q: In most of your work (video as well as illustrative) the colors red, pink, and blue are almost exclusively used. Is this primarily an aesthetic decision or is it a codified choice?

A: I’m not a great colorist and color has never been my passion. A limited palette makes coloring simpler. I just love bright pink a lot. Blue is more troubling. When I was painting a lot of Munch-esque deathbed scenes about five years ago (when my mom was sick), I started noticing this pattern emerging of the use of blue for piss and excrement and genitals. I don’t know why I did it. People are quick to point out “blue balls,” which I don’t think is my intention. (But maybe….it’s a fitting pun. I hate puns.)

Interestingly, one of my art heroes, Vienna Actionist Rudolf Schwarzkogler, was also fascinated by the color blue. Hermann Nitsch wrote of him: “Images of a cold bluish-emerald light combined with a cruel, dazzling metallic brightness were the expression of his Apollonian goals.” Maybe it’s good to have blue cooling off the hot sex organs. Maybe I’m full of Apollonian goals.

Amanda Manitach is a multi-faceted artist who balances curating art exhibitions at Seattle University’s Hedreen Gallery and writing art reviews for the City Arts Magazine. This exhibition of work will be on display at the Bryan Ohno Gallery until March 1st, 2014.

Siolo Thompson for Miroir Magazine