Q: I have heard you say that you sing because there are so many others who can’t. Can you tell us what that means?

A: As an Iranian woman raised during the reign of the oppressive regime of Iran, women in particular were stripped of many basic and fundamental human rights including the right to sing, perform and record music. This unjust continues today. Had I still been living there I would not even begin to dream of having any kind of singing career, let alone of such innovative musical explorations. Many women both older and younger than me have no such hope and so every note I sing on stage is in remembrance and acknowledgement of their lack of freedom. Of course sadly this is not restricted to Iran as oppression of women is nothing new. Even after living in Canada all my adult life I have not fully gotten used to how free I am really to explore my dreams.

Q: Trauma and a need for a safe environment hinders many women in your country from perusing the arts. Can you tell us about the challenges they face?

A: In Iran, often being a woman is enough to make one a target, regardless of what a woman is wearing; how old she is; what her level of education is; what her social status is or what she does for a living. Now add to this toxic mixture the desire to be a performer, a trendsetter, an explorer in the arts and you are then definitely asking for it: to be harassed and accused of bogus charges including spreading immorality in the Iranian society. These charges and accusations may only seem like slander but in today’s political climate in Iran, they can quickly turn dangerous where the government may decide that the woman poses a danger to the stability of the regime and so being an artist, hell, being a woman is almost a political act on its own. Many singers and musicians have been arrested, assaulted and jailed over the last 40 years. Women can not legally record vocal songs in Iran and may not perform as soloists to a mixed gender audience. Often obtaining permits for women-only shows are next to impossible with rules that constantly change. A production (theatrical, musical or other), many many months in preparation can be canceled by the whim of someone seemingly in charge, always a man. Female artists are vulnerable to rumors and their conduct and dress in both private and public sphere is heavily monitored and criticized. The challenges go on and on and are out of the scope of this interview sadly.

Q: Your family travelled to Spain when you were a teenager, was that your first experience of Morish culture?

A: Yes, and no. It was my first experience to really see the truth about the far reach of Moorish culture into Europe. While growing up in Iran these stories were thought at school but again they were always tinted with the brush of politics. Islam was praised as an all-encompassing religion that was spread wide into the west. When I traveled to Spain, suddenly it was no longer about politics but the arts, the architecture, the water fountains, the ceramic detailing, the colours, the food, and of course the music. That trip had a profound effect on me. Although it took years for me to be able to accept my trauma induced negative reactions to moorish influences in Flamenco and accept the beautify of that cultural exchange.

Q: You returned with a burning desire to learn more about flamingo but there were limited resources available, what made you pursue this regardless of all the obstacles you encountered?

A: We have a saying in flamenco community that once the Flamenco fever sets in it will never settle and that is truly what I think happened to me. Specially after returning, we went right back into living a limiting and very oppressive lives where, as an example, owning flamenco tapes like my father had would have been considered a crime. There were no classes, no one to teach them and of course no legal way of doing so even if there were and no internet or youtube. All I had was a collection of lovingly recorded set of flamenco music belonging to my dad and some that we snuck into the country from our trip to Spain, facing possible severe punishment had we been found out.

Truthfully as we had no plans to leave Iran, I had absolutely no aspirations or even dreams of ever being a performer. I just poured myself into the music and the more I listened and understood the poems the more I connected to the culture of Flamenco, resonating with how I felt, needing to call out my frustrations and anger in a similar way. And of course that was not to be, till the year 1998 when I moved to Vancouver and started studying Flamenco dance.

A: You also trained in classical piano when you were young, can you tell us why you were never able to do public performances?

A: Yes Many Iranian families despite all the challenges went out of their way to provide music lessons for their children and my brother and I were given Piano lessons. During my teen years specially I was playing piano at least 4 to 5 hours a day as it had become my main source of therapy and coping with the intense brutal totalitarian regime and how we were treated in school and in the streets every day. I was in fact given one single opportunity to perform in public as part of a group of young performers in the most prestigious theater in Tehran. A simple performance of a 5 minute piece was prefaced by hours of harassment and badgering about how I was dressed or was behaving during rehearsals and during and after the performance. It was one of the most humiliating and painful experiences of my life. I was 15. And I knew that I would never ever perform in Iran again, at least not with the current regime still in power.

Q: When your family immigrated to Canada what changed for you?

A: Everything. Absolutely everything changed. To this day I am convinced wholeheartedly that I would have either self harmed, ended in prison or become a hermit completely broken and depressed. In Canada, I attended high school for two years and for the first time ever, I experienced joy and acceptance and teachers who actually seemed invested in my success. I was given endless opportunities to learn, and explore. Facilities and resources were shared so generously and openly that it took me a long time to trust that there was no agenda. I attended endless art classes, had full access to a free high end camera, a ceramic studio and a painting space and a full library of art books that I could taken home to study to my hearts content. I started having opera voice lessons and was encouraged to perform piano as often as I was willing. I participated in two major musical theater shows in minor roles but it absolutely did not matter because I was living and breathing the arts. I didn’t know it was possible to be that happy.

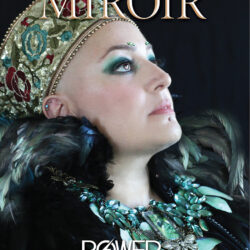

Q: What gave you the idea to use Farsi lyrics with Flamenco music, please tell us about the challenges of making that work.

A: We first immigrated to Toronto where I spent the two formative years of high school and then attended university to study Interior Design. I had continued to play the piano and have voice lessons and was a part of several wonderful choirs. But in 1998 when I moved to Vancouver as an adult, for the first time I had the time and the means to pursue flamenco and started as a dancer, never dreaming that I could also sing. In 2001 I started exploring singing (in Spanish), mostly because by then I had my first son and was expecting my second and simply did not have time to attend as many dance classes and performances. I assumed singing would keep me connected but it would be less involved. But I had underestimated my blessings which allowed me to begin performing as a singer less than a year after I had started. Since I knew the dance so well, I was able to jump right into working with dancers as a singer and my extensive musical training had prepared me in a way that was very surprising to myself as well.

The idea of Persian Flamenco came about because in 2010 I felt I needed a new challenge. I had begun to resent being compared to various flamenco singers and having to do covers of famous songs. I either had to move to Spain to push farther and deeper into the world of flamenco or come up with a way to feel challenged and satisfied artistically all over again. Since I had small children at the time and was working full time as an Interior Designer, I knew I would be staying in Canada. And so I began to explore for a way to perform that not only was intensely personal and artistically mine but also do something that neither Iranian performers or Flamenco performers could do. To fuse the two ideas in a way that only someone who had lived deeply in both traditions could really attempt. And so the journey began.

At first, in all sincerity I assumed it would be easy. I would pick a song I liked and just would change the words. My naivete was my saving grace in not understanding how challenging it would be to force such a lyrical language as Farsi to pair up with such a rhythmically intense form of music. In Classical Persian music and poetry, lyrics and the cadence of the words are the ultimate deciding factors about how a song is accompanied. In major contrast, in Flamenco rhythm is God. The words are almost always scarified in the favor of achieving rhythmical mastery. A word may be stretched and repeated so much that it will lose all meaning only so the beat or compass as it is called is supported. This act of butchery of the words would be practically blasphemous if done in Persian music!

Q: You have two teachers who guided you during the process of adapting Persian poetry to Flamenco rhythms. Tell us about this process and your determination to make it work.

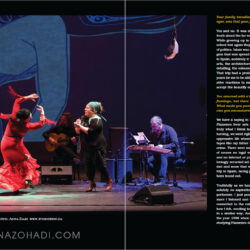

A: I have had the privilege of working with many important mentors along the way. One, Kasandra La china in Vancouver, commissioned my very first piece and set choreography to it. Oscar Nieto of Vancouver and Vicente Griego of Albuquerque who gave me “permission” to explore creating flamenco in a different language. But the main two teachers who were on the journey with me, whom I worked with in the years between 2014 and 2016 at the height of my work on my first album were Ms. Falahati, Iranian Classical singer in Vancouver and Lucas Ortega of Spain. The hardest part as I mentioned was marrying two very conflicting musical ideas. I would spend endless hours shifting the accent on a single word from the first syllable to the second or third or fourth and then back. Each time I would only satisfy either the lyrics and how they should be said or the rhythm and how flamenco demanded that the accent be on a certain beat on each word. Finding a balance between the two proved to be a tediously obsessive work of 6 years from the day I started writing my first song to October 2016 where my first album of 8 songs was published.

Q: You mentioned that the decision to pursue this path was not a simple one, but a journey of tears, and thoughtful journaling which finally led you to the point of giving yourself permission. Can you tell us more about the doubt and conflicts you faced and how you overcame it?

A: I think above all it was about the idea of aspiring to take Flamenco, such an established musical genre into a new direction where no one had really attempted successfully or to the depths I had in mind. There had been many side by side “conversations” between Flamenco and various global genres including Persian but a “one voice” approach had not really been attempted.

I could not come to terms, especially at first. Was I even allowed to sing Flamenco in a language other than Spanish? As a dancer for over 10 years, Flamenco singing was almost sacred and it was not to be touched. As I came to embrace and almost revel in the technical challenges I also worked with my mentors, recognizing and eventually internalizing my ancestral claim to the roots of Flamenco as an Iranian of Persian heritage. Recognizing how much of flamenco came from Iran and that part of the world; how many musical scales we had in common; how much of the keening of flamenco is still resembled in traditional style of singing in Iran and of course other eastern cultures … all of this freed me from listening to the ever present voice of doubt.

But when it came to choosing lyrics, even when I don’t write my own, I choose poems very carefully and that is when a lot of internal therapeutic work happened which I had not expected. Time and time again as we moved from one song to another I fell apart, I shed tears that just refused to dry as I relieved trauma after trauma, mourning my childhood, mourning for my country of birth and the oppression I still witnessed Iranians dealt with, specially women, reliving depression and anxiety I felt upon immigration at 17, having to learn English practically from zero, dealing with religious persecution and feelings of loss and betrayal and eventual joy of finding art, a new set of friends, a new home, setting own roots. That first album was purely an act of indulgence where it was to be only for me, having the chance to work through it all. I never expected it to be received in such a public and positive way. And when that happened that opened the door for another series of healing experiences because I understood my stories were not all that unique to me after all and many, especially many Iranian women had gone through very similar situations, and many were still dealing with these challenges because they were still living inside Iran.

Q: How people manage their fears and what they do with them is something you are keenly familiar with, and yet somehow you have had the courage to forge a very unique path. What advice do you have for others who might be facing similar choices?

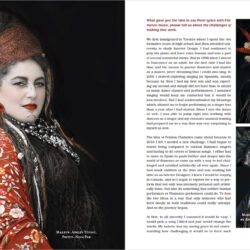

A: I think in some ways I am very blessed to be suffering from major “fear of missing out” and what I mean by that is I really got into the music game quite late in life. My first album was published when I was 43! In someways I acknowledge that it was my extensive life experiences in both musical genres that have allowed me to explore both forms but the voice of doubt I refereed to is often loud and clear, making me wish I was younger. The fear is a combination of having missed my prime as a newcomer to the music world, and also the fear that what I am trying to achieve is actually not good enough and me not having enough time in life to mend things and make it better.

But the most important win is being surrounded by positivity and people who are trail blazers themselves. This is extremely important and in many ways crucial. So that is the first advice: Look for the right people to surround yourself with. Those who say “YES” first and then will ask the “HOW”. Those who see the light of your passion and your dream in your eyes and want to fan the flames and take joy in your success. I have been told often that this is easier said that done, however when we are open and ready to receive, the right teachers will come along almost magically ready to guide. It has happened to me so often that I no longer question the wisdom of it. I just put my feelers out and it happens. So yes, the fear is there, it will never go away. In fact I might be arrogant enough to say, without it being frightening it is not even worth doing. And then that brings us back to the fear of missing out. If I wanted to feel safe and secure and stay in my comfort, I would not have sought something to make me feel so alive. So feel the fear but do it anyway. That is absolutely my motto. If your work, your passion and ideas are authentic and worthy to you specially, it will never be a loss exploring them. Face the worst thing that can happen, mockery? not being accepted? If the work is true to YOU, no one will ever be able to question it. They might choose that it is not for them but they will know that ultimately it is your truth. And there is no braver thing that attempting to live ones truth.

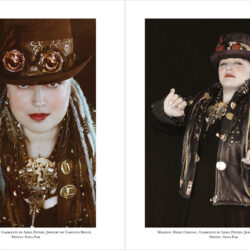

Q: What about vulnerability and giving yourself permission to not be perfect?

A: That is the blessing of age! HAHA!! But truthfully, recognizing that everyone is struggling and deep down everybody is vulnerable and only wants to be seen and accepted is truly freeing. Everyone has demons, big and small. People are often too preoccupied with their own stories to pay much attention to mine. So then I say the things I need to say because not many really care but the few that do, will connect with the truth of it. Perfection is not real. Specially in the arts, its very humbling in many ways to be an artist. No produced art is ever as perfect as it is when it’s still speculating in your brain. And so we humble ourselves, accept the next best thing that we can produce as close to what is in our minds and move on to the next creation. So inevitably we learn again and again to accept the imperfections and strive once again for the realization of our next wondrous idea. I think this pattern can be adopted to other areas as well, like how we look at our physical body or how we assume others see us.

Q: You have a ritual before you go on stage which starts with the phrase “remember how it was before.” Tell us why you do this and what it means.

A: Yes, I still do that to this day and it helps to ground me and remind me of the journey. I know it sounds cliche and in some ways I am impatient to get to where I aspire to be with my music but the journey is extremely important. It has been the only path I could have taken to bring me this far. Had I not had experienced all the traumas, all those interactions with toxic misogyny and politicized religion, and oppression, and hearing “No” over and over and over again, I would not be able to connect to my lyrics the way I do. And I would not be able to look at another Iranian and know that we are bonded over shared and unspoken experiences. I get many emails and messages and in person after concerts from women specially who either recount their regrets about not being able to follow their hearts’ desire to sing or create art or know of someone who has had that experience. The privilege is intensely immense and I am very very aware of it. Things so easily could have gone another way but here I am, having lived this marvelous life and now living my truth. And so yes, I remember how it was and how it could have been and how it is changing and evolving and how it will be and then I step on that stage, big or small and I can allow the music to take over.

Q: You have produced several solo albums, the first which took six years to complete. Can you tell us a little about the challenges you encountered along the way?

A: The first challenge was of course as I mentioned the absolute refusal of Persian lyricism to marry flamenco! But I am stubborn to a fault if nothing else and I have brought them peace. In a way, when the first album took 6 years and writing songs each were a one year or more process, I have been able to write so much faster and with so much more ease. The music flows now, there is no war, only harmony and conversation and eventually I hope a cohesive single voice which to me is the ultimate idea of fusion music, where it’s impossible to tell when one genre ends and the other begins.

I would have to say the biggest challenge I have had has been finding the musicians skilled enough to bring along this path. It is not for the faint of heart and even when there is enthusiasm it requires a specialized set of skills to contribute musically to songs I have been writing and would like to write in the future. This has brought me in contact with musicians of many backgrounds, and nationalities and locations in the world, always searching and looking. This of course requires funds and willingness to wait for logistics to fall into place, not to mention that sometimes finding a particular musician who can actually play well enough to add to the conversation is next to impossible. In the recent years I have gotten better at spotting the right musical partners. I have also been blessed to be getting some grants from Canadian Art Resources like Music BC and Canada Council for the Arts. The hustle is real but the results are tremendously satisfying.

Q: What comes next?

A: Well, I have just begun a second year of studying traditional flamenco in Sevilla, Spain. I felt that I needed to solidify my fundamental knowledge and it was time. But I am also pursuing the Persian Flamenco project with more passion than ever, working towards releasing my fourth album on March 8th, 2023, on International Women’s Day. It seems the European audience has an easier time understanding and digesting what I am trying to do, having been familiar with Flamenco intimately and longer than North Americans. The album will be launched along with a European tour. I am planning several collaborations with many of my flamenco idols and its very encouraging to see that the project is received again and again in such a positive way even by many traditional flamenco artists.

Also, as we conduct this interview (September 2022), Iran is experiencing its “George Floyde” moment where thousands upon thousands of Iranian women and men have taken to the streets fighting for their freedom and to be rid of the current regime. Having been affected all my life by their archaic restrictive laws, I can not be more excited about what future holds for women of Iran and I can now put it out into the universe that I will be back one day to perform there where I was denied so many times. Amen.